POLICY WORK GROUP PAPERS

What Would Make a U.S. Single-Payer Healthcare System as Cost-Effective as Other Advanced Countries?

By Stephen Kemble and OPS Policy Working Group 2020

U.S. healthcare is the least cost-effective in the developed world, by far, with widespread failures in both access to care and cost control. The COVID-19 pandemic has also exposed the serious flaws in financing health care through employment and from state taxes, both of which have dropped precipitously. The urgency has never been greater for consideration of a single-payer healthcare system for the U.S., financed with federal tax revenues.

Recent cost estimates of a U.S. single-payer system at either the federal or state level vary wildly in their assumptions, predicting anywhere from 18% increase in cost (Urban Institute 2019) to 18.8% savings (Friedman 2019). Other countries with universal health care systems, both single-payer and regulated multi-payer, spend 40-60% of what we do on healthcare as a percentage of gross domestic product, so clearly the assumptions behind U.S cost estimates do not match the policies actually used in other countries.

We know the difference between the U.S and other advanced countries is not excessive utilization of care, which is toward the low end of the range in other countries. The difference is in administrative complexity and lack of effective price controls, driving higher prices. “Administrative complexity” includes widespread profiteering by layer upon layer of middle-men: insurance companies, Medicare Advantage plans, Medicaid managed care contractors, Health Maintenance Organizations, Accountable Care Organizations, hospital-physician chains now taking on insurance risk, pharmacy benefits managers, revenue-cycle managers, and their contractors and sub-contractors.

Current healthcare reforms in the U.S. are founded on the belief that excessive utilization driven by incentives in fee-for-service payment is the major driver of excessive cost in U.S. health care. The proposed solution is to shift insurance risk onto doctors and hospitals in the form of capitation and bundled payments, so that they make more money by providing fewer services, and hopefully only services that have “value.” The experience of other countries that pay for health care with fee-for-service and spend half what we do per capita certainly should raise questions about the assumptions behind “value-based” payment.

Although there are pockets of over-utilization driven by fee-for service, most notably in the hospital sector with some procedural specialists, there has never been any evidence of over-utilization of primary care services with fee-for-service payment. However, efforts to shift from fee-for-service to capitation, led by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), have been focused largely on primary care. The result so far is widespread demoralization and a worsening shortage of primary care physicians nation-wide.

Value-based payment (shifting insurance risk onto providers of care) introduces unwanted incentives to skimp on care and avoid care of sicker, more complex, and socially disadvantaged patients and populations (“cherry picking” and “lemon dropping”). The counter-incentives are pay-for-quality or outcomes, and risk adjustment. Both of these are far too complex to do accurately, and they are failing to deter skimping on care and “cherry picking” by health systems, hospitals, and doctors. Furthermore, both pay-for-performance and risk adjustment require much more detailed documentation and data reporting than is required by fee-for-service, raising administrative cost and burdens. So far, Medicare’s ACO program is costing as much or more to administer than the very modest savings achieved from reduced utilization, and the cost and burdens of increased documentation and data reporting are the main cause of widespread physician “burnout” and the destruction of independent primary care. Administrative cost is also driving many early participants in the ACO program to drop out.

This brings us back to the question, “What design features of a U.S. single-payer system would reduce our per capita healthcare cost to the range found in other advanced countries?” Desirable features of such a system should include public accountability, transparency, and meaningful public participation. We propose the following principles, based on what has been shown to work in other countries and in the U.S. None are characteristic of current U.S. healthcare policies.

Assure access to high quality care for everyone equally. Make every effort to eliminate disparities in access to care. Finance health care with progressive funding sources and eliminate or severely minimize patient cost-sharing. However, achieving universal coverage and eliminating disparities cannot be achieved politically without cost containment.

Cost containment should be achieved primarily by reducing administrative costs and reducing structural incentives to provide services that may not be most effective, not by interfering in the doctor-patient relationship. Reducing administrative costs will allow lower fees. Monopsony power must be used to more effectively control prices of prescription drug and medical equipment.

The key to administrative simplification and savings is standardization of payment and price controls, not competition, profit incentives, micromanagement of care by health plans, or use of financial "carrots and sticks" to manipulate doctors and hospitals in the name of "improving" health care.

Standardized payment of doctors and other healthcare professionals requires a mechanism to keep payment in proportion to the training and expertise required for each profession. The most efficient and effective means to assure this would be collective negotiation of salaries for employed doctors and other health professionals and fees for those in independent practice, between the single-payer and organizations representing each profession. Likewise, prices for pharmaceuticals and durable medical equipment must be standardized and negotiated between the single-payer and manufacturers of drugs and DME.

Manage insurance risk by maximizing risk pooling with a single risk pool, not competition among plans that each have their own risk pool, or by creating networks and shifting insurance risk onto doctors and hospitals within those networks. Risk-shifting creates perverse incentives to skimp on care and avoid care of sicker, poorer, and more complex patients and populations, aggravating disparities in access to care.

Health care must be a public good, not a commodity purchased according to ability to pay, or a "feeding trough" for those seeking to extract profit from health care, and it should not be owned or organized or managed by large corporations with business motives and ethics, whether technically for-profit on non-profit.

Establish and maintain a robust public health system, including programs for prevention of disease, responding to environmental disasters and pandemics, and addressing linkages between health care and social determinants of health.

Promote professional ethics and intrinsic motivation for doctors and other health professionals. The desire to improve patient care must be the basis for quality improvement, not financial incentives (pay-for-performance). Keep payment for health care as incentive neutral as possible, so as to free up professional ethics and intrinsic motivation. The incentive-neutrality principle prohibits capitation, shared savings payments, pay-for-performance etc. because they require accurate risk adjustment which is not possible and drives up administrative costs.

Payment for both doctors and hospitals must be disconnected from the details of documentation. Payment of doctors should be based on their time and expertise, not on counting “elements” in their notes. Medical documentation should be focused on information necessary for patient care and quality improvement, not “pay-for-documentation.” The administrative burdens of inappropriately detailed documentation and data reporting now required for pay-for-performance and risk adjustment are the root cause of widespread physician demoralization and “burnout."

One Payer States Policy Work Group Model Legislation “White Paper”

By Stephen Kemble and Kip Sullivan

April 2020 [draft 9 (clean)]

Hospital Payment Under Single-Payer Proposals: Payments to Risk-Bearing Entities Versus Budgets for Hospitals

1. Should single-payer proposals authorize competing risk-bearing organizations by any name (accountable care organizations, HMOs, integrated delivery systems)?

2. Since it is not possible to pay hospitals simultaneously with budgets and through risk-bearing entities, by which method should hospitals be paid?

Competing Risk-Bearing Organizations

Can or should a single-payer system at either the state or federal level include Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), “Integrated Delivery Systems (IDSs)” or any other competing entities or systems that bear insurance risk?

The OPS Policy Working Group defines insurance risk-bearing entities as organizations that

have specified enrollees or assignees/members, and

have a contract with either each enrollee (premium paying subscriber) or with a payer contracting on behalf of enrollees that obligates the organization to pay for all necessary medical services needed by their enrollees over a given time period.

For the past several decades, efforts to control excessive health care costs in the U.S. have been built on the fundamental ideas of shifting insurance risk onto providers of care and competition among risk-bearing entities, but the combination of these strategies introduces serious perverse incentives. In health care, too much of financial risk is predictable due to pre-existing conditions, socio-economic status, and demographics. Competing risk-bearing entities soon find that the key to economic survival is not to offer better benefits and improved access to care, but to capture a healthier than average risk pool and to drive higher risk individuals and populations out of their risk pool and onto the competition.

Since its emergence in the early 1970s, the managed care movement’s most fundamental objective has been to shift insurance risk onto doctors and hospitals. Managed care advocates at first promoted HMOs as the ideal mechanism for risk-shifting, but they have since promoted several other vehicles that do not differ substantially from HMOs, including ACOs and IDSs. Advocates of HMOs, ACOs, and IDSs base their support for these entities on the assumption that the high cost of health care in the US is due to over-utilization of health care, and this in turn is caused by the fee-for-service method of payment.1 This diagnosis of the problem suggests that the problem could be solved if the fee-for-service incentive were turned upside down, that is, if insurance risk were shifted onto doctors and hospitals so that they make more money by delivering fewer services and supposedly only services that have “value.”

Although some overuse of some services exists, the theory that over-utilization explains high U.S. health care costs has never been supported by evidence. Compared to other advanced countries with universal healthcare systems that cover everyone, largely use fee-for-service payment, and cost half what we spend, U.S. per capita physician visits and hospital utilization rates are low2. A far bigger problem in the U.S. is lack of access to needed care and under-utilization, leading to costly complications. There is now extensive evidence that the high cost of health care in the U.S. is caused primarily by much higher prices, which are in turn driven by excessive administrative costs and the absence of effective price regulation3,4,5.

HMOs and other risk-bearing entities achieve little or no reduction in medical costs, and little or no improvement in quality6,7,8. However, the tools required for management of insurance risk, including pay-for-performance and risk adjustment, depend on detailed documentation and data reporting that have resulted in markedly increased administrative costs and burdens for physicians9 and hospitals5 as well as for the HMO, ACO or IDS10. And yet, despite this poor track record, HMOs, ACOs, and IDSs are still being promoted today as cost-cutting strategies. Proponents of this view include the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the insurance industry, state Medicaid programs, and authors of some bills that resemble single-payer legislation1,11. We recommend against including any of these risk-bearing entities in what would otherwise be single-payer legislation. Doing so will simply replicate the wasteful competitive insurance business model the single-payer proposal was designed to replace. The fact that many ACOs and IDSs are owned by, or have contracts with, insurance companies is perhaps the most compelling evidence for this statement.

Reducing the high administrative cost of the current multiple-payer system is essential to the success of any single-payer proposal at either the state or federal level. Any proposal that only expands coverage but does not achieve substantial administrative savings will likely die in the legislative process, especially when, at the national level, it gets a score from the Congressional Budget Office.

Reliance on competing risk-bearing entities worsens disparities in access to care for patients. American insurance companies and other risk-bearing entities have demonstrated that they compete by using strategies to capture a healthier than average risk pool (commonly referred to as “cherry-picking”) and driving higher-risk individuals and populations out of their plan or network and onto the competition (often referred to as “lemon-dropping”)6. Examples include marketing to healthy people, patient cost-sharing, offering benefits that favor healthy non-poor people (such as gym memberships and Fitbit programs), eliminating benefits or programs or formulary drugs for expensive chronic conditions, restricting networks to exclude doctors who specialize in treating expensive conditions, creative parsing of risk pools into different plans for different customers, and denying necessary care, all of which result in declining access to care for sicker and socially disadvantaged individuals and populations.12

Cherry-picking and lemon-dropping clearly worsen healthcare disparities. However, the insurance industry and other advocates of shifting risk onto doctors and hospitals have argued for decades that cherry-picking and lemon-dropping can be eliminated by adjusting per-enrollee payments to reflect the health of enrollees, a process known as “risk adjustment.” In theory, risk adjustment adjusts premium/capitation payments to reflect factors that can affect health that are outside the entity’s control such as the enrollee’s pre-existing conditions, age, income, education, ability or willingness to exercise, exposure to stress at home or work, genes, etc. But despite a half-century of research, risk adjustment remains very crude and exceedingly complex.

Consider the gross inaccuracy of the most widely used risk adjuster in America – the Hierarchical Condition Categories formula that CMS uses to adjust payments to Medicare Advantage plans and ACOs that participate in Medicare13. In theory, accurate risk adjustment should remove the incentive to cherry-pick and lemon-drop because then the risk-bearing entity would receive no reward for doing so. Risk adjustment will supposedly claw back all profits from those that cherry-pick and lemon-drop and, conversely, it will protect those that enroll an above-average share of the sick. However, the CMS risk adjustment formula captures only about 12 percent of observed cost variation in spending among enrollees. It overpays for the healthiest 20 percent of enrollees by 62 percent and underpays for the sickest 1 percent by 21 percent. [MedPAC June 201414] The result is that doctors15, hospitals16,17, and health plans18,19 engage in cherry-picking, lemon-dropping, and gaming of documentation to make patients appear sicker in order to beat risk adjustment formulas and increase their reimbursement.

It is not possible to increase the accuracy of risk adjusters substantially, and any attempt to do so requires a prohibitive escalation in provider administrative costs and burdens14,18. The reason risk adjustment is so crude, and so difficult and expensive to improve, is two-fold: (1) the factors that affect human health, and therefore the cost of treating humans when they get sick, are numerous and very complex; (2) it is financially and technically impossible to identify all relevant factors, collect data on all those factors, and calculate their relative contributions to the cost of medical care.

If risk-shifting actually resulted in in better health outcomes, the high cost of risk-shifting and crude risk adjustment might be justifiable. The evidence does not support that claim. There are much more effective strategies to promote quality improvement that rely on the intrinsic motivation of physicians and other health care professionals to provide high quality care for their patients. Quality improvement metrics that are developed and modifiable by front-line providers of care and do not rely on financial incentives have been shown to be effective20,21, and cost far less to administer than pay-for-performance administered by health plans. Likewise, care coordination is best handled by front-line physicians in a unified, open care delivery system in which all specialties and consultants are available to every primary care practice, instead of by competing health plans with restricted networks, run by administrators who do not have specific knowledge of the needs of individual patients.

To the extent that the research does support certain interventions (for example, nurses staying in touch with patients after discharge, interdisciplinary team-based care of complex patients in the community, specialized programs for substance abuse or the seriously mentally ill, and many specialist consultations), we support paying nurses, doctors, and other health care professionals directly through community based programs paid with global operating budgets to provide those services, rather than paying HMOs/ACOs/IDSs a per-enrollee fee and hoping some of the money winds up being used to provide such services.

2. Should hospitals be paid with global budgets or through competing risk-bearing entities?

The OPS Policy Working Group has concluded that:

hospitals should be paid individually (not as members of chains),

hospitals should be paid via budgets, not via payments per enrollee (premiums, capitation payments, shared-savings payments, or any other form of payment that shifts insurance risk off the single government insurer), and

hospital budgets must be divided into capital and operating budgets.

In order to achieve the maximum reduction in system administrative costs and to give society control over the allocation of hospital resources, single-payer legislation must authorize budgets for hospitals; but hospital budgets are not feasible in a multiple-HMO/ACO/IDS system.

The OPS Policy Work Group recommends that model single-payer legislation control expenditures for hospitals and other institutional providers (hereinafter referred to simply as “hospitals”) with budgets for hospitals that meet these criteria:

they apply to individual hospitals, not groups of hospitals or hospital-clinic chains that are part of HMOs, ACOs, or IDSs;

they are based on factors such as the historical volume of services provided, actual expenditures, comparison to other hospitals in the area, projected administrative savings from billing and collections, projected changes in volume and type of services, wages for employees, maintaining recommended staffing-to-patient ratios, education and prevention programs, quality improvement, adjustments to improve access to shortage specialties and to correct disparities in access to care, and adjustments to respond to epidemics and natural disasters; and

they are divided into operating and capital budgets.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal’s HR 138422 contains a provision that permits outpatient physician groups that have contracts with nearby hospitals to be paid through the hospital's global budget. Including such groups in budgets for individual hospitals is acceptable. Doing so would not shift risk on to providers (that is, there would be no need to enroll patients and pay the hospital on a per-enrollee basis). Patients would remain free to see any qualified provider in the community, and hospitals and medical group practices that chose to organize under a single global budget would not be closed systems like Kaiser Permanente and other HMOs are now. However, this provision would enable physicians to be paid with salaries instead of with fee-for-service.

Hospital budgets reduce health care costs primarily by reducing hospital administrative costs. They do so by eliminating the cost of assigning expenses to each patient and the complex claims adjudication process this now requires. Research has shown that single-payer systems can cut hospital administrative costs in half if they set budgets for hospitals (as Canada and Scotland do), and by smaller amounts if the system pays hospitals on a per patient basis23.

Moreover, splitting hospital budgets into operating and capital budgets, coupled with the requirement that budgets be negotiated with individual hospitals, gives society control over the allocation of both operating and capital expenditures. In our view, society, not the executives of hospitals, chains, HMOs and other risk-bearing entities, should decide whether to open or close a hospital in a low-income community, to close an ob-gyn department or an addiction clinic in a rural town, or to expand needed services to correct shortages. If we want society to make those decisions, then our model legislation should not authorize the single-payer governing board to negotiate budgets with hospital chains. If it did so, the CEO of those chains could decide where to allocate emergency rooms and other resources within the chain. If society is to control resource allocation, each hospital has to be given its own budget.

At present, hospitals rely on budget surpluses to fund capital improvements and improve their competitive positions, and this drives promotion of profitable service lines for well insured patients at the expense of services that lose money, no matter how necessary they are to the surrounding community. Separating hospital budgets into operating and capital improvement budgets, with no profit carried over year to year allowed, assures that operating budgets are only for hospital operations, and capital improvement funds are allocated according to community need.

Budgeting for individual hospitals also removes funding streams that hospitals now use to join or create chains that primarily serve business goals and investors. The consolidation of the U.S. health care system into fewer and larger entities has played a significant role in driving U.S. per capita costs far above those of the rest of the industrialized world24,25,26.

Some single-payer proposals, such as Sen. Sanders’ S180427, the Healthy California Act, the New York Health Act, and the Massachusetts Medicare-for-All bill all retain risk-bearing entities by various names (HMOs, ACOs, or IDSs) as their “cost saving” measure. Such bills typically do not authorize budgeting of hospitals, presumably because it is not possible to both set premium/capitation payments for HMOs, ACOs, or IDSs that include hospital care and also set budgets for individual hospitals. If hospitals are paid via operating and capital budgets negotiated with a single payer, then their budgets are entirely accounted for. It makes no sense for the single payer to attempt to budget an HMO, ACO, or IDS that includes services provided by the same hospitals that have already been fully funded.

If the excessive cost of U.S. health care is to be brought into the range of all other industrialized countries, we must emulate policies that have been proven to work somewhere. Hospitals should be paid with separate operating and capital budgets allocated by a single-payer, not payment for each service and item used by each patient from multiple payers, each of which makes up their own payment system and rules.

Insurance risk is most cost-effectively managed by establishing a single risk pool for an entire population and markedly simplifying the payment system, not shifting risk onto doctors and hospitals, fragmenting risk pools in ways that worsen disparities in health care, and competition that rewards avoiding sicker and socially disadvantaged patients and gaming of medical documentation. Broad risk pooling, simplified payment policies, and global budgeting of hospitals will create large administrative savings that can make a single-payer proposal cost-effective, and therefore more politically feasible, than universal coverage proposals that rely on the unproven theory that competition between risk-bearing entities will somehow reduce costs.

References:

Schroeder SA, Frist W. Phasing Out Fee-for-Service Payment. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2029-2032.

OECD iLibrary, 2019. Healthcare Utilization. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_PROC

Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries. JAMA. 2018;319(10):1024–1039. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.1150

Himmelstein DU, Campbell T, Woolhandler S. Health Care Administrative Costs in the United States and Canada, 2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 172(2):134-142. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-2818

Chernew ME, Frakt AB. New Research Spotlights Different Drivers of Spending Growth In The Public And Commercial Sectors. Health Affairs Blog. Feb 15, 2019. 10.1377/hblog20190213.201103

Markovitz AA, Hollingsworth JM, et al. Performance in the Medicare Shared Savings Program After Accounting for Nonrandom Exit. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:27-36. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-2539

McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early Performance of Accountable Care Organizations in Medicare. N Eng. J Med 2016; 374:2357-2366.

Gonzales S, Ramirez M, Sawyer B. How does U.S. life expectancy compare to other countries? Kaiser Family Foundation. December 23, 2019.

Casalino LP, Gans D, Weber R, et. al. US Physician Practices Spend More Than $15.4 Billion Annually To Report Quality Measures. Health Aff 2016;35(3):401-406.

Sanborn BJ. Change Healthcare analysis shows $262 billion in medical claims initially denied, meaning billions in administrative costs. Healthcare Finance News June 27, 2017.

Lewis VA, Fisher ES, Colla CH. Explaining Sluggish Savings under Accountable Care. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:1809-1811.

Rubin R. How Value-Based Medicare Payments Exacerbate Health Care Disparities. JAMA.2018;319(10):968–970. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0240

Pope GC, Kautter J, Ingber MJ et. al. Evaluation of the CMS-HCC Risk Adjustment Model. CMS Office of Research, Development, and Information. March 2011.

Improving risk adjustment in the Medicare program. MedPAC Report to the Congress, Chapter 2: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, June 2014.

Doran T, Fullwood C, Reeves D. et. al. Exclusion of Patients from Pay-for-Performance Targets by English Physicians. N Engl J Med 2008;359:274-84. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa0800310

Farmer SA, Black B, Bonow RO. Tension Between Quality Measurement, Public Quality Reporting, and Pay for Performance. JAMA (2013);309(4):349-350. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.191276

Himmelstein D, Woolhandler S. Quality Improvement: ‘Become Good at Cheating And You Never Need to Become Good at Anything Else’. Health Affairs Blog. August 27, 2015.

Pope GC, Kautter J, Ellis RP, et. al. Risk Adjustment of Medicare Capitation Payments Using the CMS-HCC Model. Health Care Financing Review 2004; 25(4):119-141.

Kronick R. Projected Coding Intensity in Medicare Advantage Could Increase Medicare Spending by $200 Billion Over Ten Years. Health Affairs 36, no.2 (2017):320-327. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0768

James BC, Savits LA. How Intermountain Trimmed Health Care Costs Through Robust Quality Improvement Efforts. Health Affairs 30, no. 6 (2011):1185-1191.

James BC. Clinician-Directed Performance Improvement: Moving Beyond Externally Mandated Metrics. Health Affairs 39, no 2 (2020):264-272.

H.R.1384 - Medicare for All Act of 2019. Sponsor: Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA-7)

Himmelstein DU, Jun M, Busse R, et.al. A Comparison of Hospital Administrative Costs in Eight Nations: US Costs Exceed All Others by Far. Health Affairs 33, no. 9 (2014): 1586–1594.

Post B, Buchmueller T, Ryan AM. Vertical Integration of Hospitals and Physicians: Economic Theory and Empirical Evidence on Spending and Quality. Medical Care Research and Review 75(4) (2018): https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1077558717727834

Ho V, Metcalfe L, Vu L, et.al. Annual Spending per Patient and Quality in Hospital-Owned Versus Physician-Owned Organizations: an Observational Study. J Gen Intern Med 35, 649–655 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05312-z

Goldsmith J, Burns LR, Sen A, Goldsmith T. Integrated Delivery Networks: In Search of Benefits and Market Effects. Natl Acad of Social Insurance. Feb 2015

S.1804 - Medicare for All Act of 2017. Sponsor: Sen. Bernard Sanders (I-VT)

Optimizing payment of physicians for a single-payer healthcare system

By Stephen Kemble, MD and One Payer States Policy Work Group Version: Oct. 29, 2020

Introduction:

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a sharp drop in health care funding through employment and from state taxes, making consideration of a federally funded single-payer healthcare system for the U.S. more urgent than ever. A federally funded system would be much better positioned to weather economic downturns, and single-payer reform would offer opportunities to reduce the enormous administrative complexity that is a major driver of excess cost in U.S. health care.

A single-payer system will require a method for paying physicians in independent practice who do not have an employer. This paper discusses problems with current methods used by Medicare and adopted by other payers and proposes an alternative payment methodology that would replace Medicare’s Resource Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) with a fee- determination system that would price medical services based on the time and expertise of the professional performing each service or procedure instead of attempting to calculate an inherent relative value for each procedure. We believe this proposal would be substantially simpler, more incentive-neutral, and less costly to administer than current methodologies.

Problems with physician payment methods now in use in the U.S.:

The three broad models in use for physician payment are salaries for physicians employed by hospitals and other institutional providers of care, fee-for-service for most payments to independent physician practices, and capitation, or payment per attributed person instead of per-visit or per-service. Capitation is the most complete form of shifting insurance risk onto doctors, but partial forms of risk shifting, collectively referred to as “value-based payment,” can be added to a foundation of fee-for-service payment. These include financial incentives based on cost or outcomes of care and bundled payments for episodes of care.

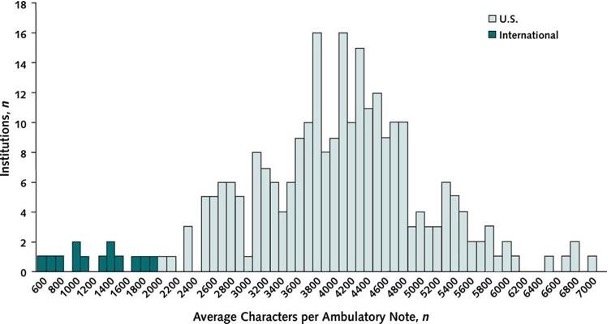

Since 1992, Medicare has based fee-for-service fees on the Resource Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS), later modified to include so-called “value-based payment” reforms designed to shift insurance risk onto health plans, hospitals, and doctors to induce them to restrict care. Almost all other U.S. health plans using fee-for-service base physician payment on modifications of Medicare fees. The RBRVS has relied on the details of documentation to determine fees for cognitive services, creating a financial incentive for over-documentation, and this has been greatly compounded by the introduction of electronic health records geared more toward payment than patient care. Value-based payment reforms have added further administrative burdens because shifting insurance risk onto doctors requires pay-for-performance and risk adjustment, both of which depend on detailed documentation and data reporting. The length

of medical notes in the US are on average about three times the length of those in other countries that use the same electronic health record, but do not rely on pay-for- documentation. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

Figure. Average characters per ambulatory progress note in U.S. and international health systems.

Column height represents number of organizations. Dark columns represent 13 organizations outside the United States (140 000 notes from Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, the Netherlands, Denmark, the United Arab Emirates, and Singapore). Light columns represent 254 organizations in the United States (10 million notes). Downing e. al. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(1).

Problems with U.S. payment methodologies include administrative complexity, over-valuing procedures relative to cognitive tasks and services, gaming of documentation for payment, loss of physician control over their time due to payers requiring excessive unreimbursed documentation time and administrative tasks, inequities in patient access and quality of care, and financial incentives that often interfere with a physician’s intrinsic motivation and best judgment about patient care. None of these problems are inherent to fee-for-service, but are a result of the particular fee-for-service methodology used by Medicare and adopted by other payers in the U.S.

A 2016 “time and motion” study of 4 specialties (family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics) found physicians were spending twice as much time on computer and administrative tasks as paying attention to their patients. Some computer time overlaps with billable patient visit time, but excessive uncompensated administrative tasks effectively cut fee-

for-service hourly pay in half. This has become a major cause of demoralization for the physician workforce, especially in primary care specialties.

A single-payer system would be ill served by simply adopting current payment methodologies. This paper will focus on payment of independent physicians with fee-for-service, capitation and other variants of “value-based payment,” and combinations of these. We will propose an alternative fee-for-service payment system that would minimize interference with patient care and would be far less costly and cumbersome to administer.

Fee-for-Service Payment as implemented by Medicare using RBRVS:

Since 1992, the Medicare fee schedule has been determined by the Resource Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS), updated regularly by the resource-based relative value scale update committee (RUC), convened by the American Medical Association with representation from multiple specialties in a proprietary process. The RBRVS attempts to rationalize payment by calculating a fee for each procedure, with components based on “Relative Value Units” (RVUs) for work, practice expense, and malpractice liability, plus a geographic adjustment for cost of living. All of these components except the malpractice RVU have turned out to be problematic.

The methodology of the RBRVS has led to marked over-payment for procedures compared to cognitive services, and the RUC has never effectively corrected this imbalance or accurately updated practices expenses and the geographic practice cost index. Prior to 2015, the RUC was constrained by Congress’ budget neutrality rules and the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula, so that increasing primary care pay would have to be taken from specialist pay, while all fees were threatened with drastic reductions by the SGR formula.

Since passage of the Affordable Care Act, correction of fee-for-service has been sidelined by efforts to move away from fee-for-service toward value-based payment, and by the replacement of the SGR with the MACRA law and MIPS in 2015. This new law imposes pay-for- performance and pushes doctors to join Alternative Payment Models such as Accountable Care Organizations that can accept insurance risk, along with substantial increases in data reporting required for “value-based” payment. The result has been steady increases in physician time required for documentation, data reporting, and administrative demands.

Work RVU:

Criteria for determining the Work RVU include physician time, skill, judgment, stress, and amortization of physician education cost, but many of these are subjective and vulnerable to inter-specialty lobbying on the RUC, which is dominated by specialists. As a result the Work RVU is skewed toward procedures at the expense of cognitive services that predominate in primary care specialties. Primary care physicians are paid far less than many procedural specialists, and often not enough to cover medical school debt, practice startup costs, and leave enough for a reasonable middle-class lifestyle.

The time element in calculating the Work RVU has been based on surveys of a very limited sample of physicians and has not been updated regularly, raising serious questions about its validity.

The Work RVU for cognitive services uses Evaluation/Management coding that has relied on a complex “pay-for-documentation” scheme that rewards over-documentation and has only paid for patient visits, leaving time for documentation and care coordination largely uncompensated. CMS is now planning to move away from reliance on details of documentation for E/M services and allow more use of time-based coding in 2021, which should help reduce documentation “bloat.”

Practice Expense RVU:

The Practice Expense RVU has also relied on limited physician surveys, an unreliable source of data, and has not been updated nearly often enough to reflect actual practice expenses.

The Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI) uses a very complex mathematical formula and also relies on limited physician surveys, and has never been updated accurately. For example, cost-of-living in Hawaii is among the highest in the country, yet the Hawaii Medicare GPCI is mid-range.

The RBRVS is essentially a system for pricing procedures, instead of a system for paying physicians for their time and expertise, as is the case for all other highly trained professions and also for physicians who are salaried employees of hospitals and other care delivery institutions.

Value-based Payment:

Current health care reforms in the U.S., collectively referred to as “value-based” payment, have been founded on the theory that the high cost of U.S. health care is caused by overutilization due to financial incentives inherent in fee-for-service payment. This ignores the fact that U.S. physician visits and hospital days per capita are at the low end of the range of utilization in other advanced countries that cover everyone, often use fee-for-service payment, and spend around half of what the U.S. spends per capita on health care.

Although there are pockets of over-utilization driven by fee-for service, most notably in the hospital sector and with some procedural specialists, research finds much more under- utilization than over-utilization in the U.S., due to lack of access and financial and socio- economic barriers to care, often leading to costly complications and over-utilization of emergency rooms and preventable hospitalizations. There has never been any evidence of over-utilization of primary care services when paid with fee-for-service, yet “value-based” reform efforts have been focused primarily on primary care.

The “value-based” solution to presumed over-utilization is to shift insurance risk onto doctors and hospitals in the form of pay-for-performance, capitation, and bundled payments, so that they make more money by providing fewer services, and hopefully only services that have “value.” Unfortunately, capitation and risk-shifting reward skimping on care and avoidance of sicker, more complex, and poorer patients and populations who are likely to need costly care. Proponents of “value-based” payment offer pay-for-quality or outcomes and risk adjustment to counter these perverse incentives, but both quality and risk are far too complex to measure accurately, and the crude measures in place divert physician time and effort to meeting metrics that often do not coincide with patient priorities.

Crude risk adjustment also fails to deter avoidance of difficult patients and gaming of documentation. Capitated doctors soon find the keys to financial success are to maintain a large practice of relatively easy patients who don’t require too much of the doctor’s time, code their patients as intensively as possible to beat risk adjustment formulas, and try to avoid taking on more challenging patients who are likely to need a lot of the doctor’s time or require expensive care.

Risk adjustment is required when insurance risk is shifted onto capitated private plans within

Medicare and Medicaid or onto doctors and hospitals under “value-based” payment reforms. The data demands of pay-for-quality and risk adjustment in turn require a marked increase in detail and complexity of documentation and diagnosis and procedure coding, adding ever more uncompensated physician time spent on documentation and administrative tasks.

Administrative simplification is crucial to achieving a more cost-effective healthcare system. Due to their high administrative cost and exacerbation of disparities in care, we do not find “value-based” payment, pay-for-performance, shifting insurance risk onto doctors, or competition among risk-bearing entities such as Accountable Care Organizations and Medicare Advantage plans to be equitable or cost-effective strategies. We recommend eliminating all such provisions from payment for health care services. Quality improvement should be founded on the intrinsic motivation of health professionals to improve patient care, not financial incentives and disincentives.

What happens when primary care physician pay is inadequate for the training, expertise, and practice costs required?

Third party payers generally control physician fees unilaterally.

With fee-for-service based on the RBRVS, when fee increases fail to keep up with education debt, rising cost of living, and rising practice expenses, including uncompensated administrative burdens imposed by payers, then the only way primary care physicians can maintain their incomes is by increasing volume of patients seen. Since their time is limited, this means reducing time spent with each patient and limiting the number of problems addressed in a visit. Both primary care physicians and patients complain about this. Primary care physicians we know refer to this as the “fee-for-service treadmill,” and it accounts for the willingness of many of them to consider capitation, in which payment is not directly tied to the number of visits.

With capitation, physicians get a set amount of money per attributed patient per month. If the capitation rate is inadequate and does not keep up with rising practice costs, administrative burdens, and cost-of living, the only way physicians can maintain their incomes is to increase their panel size, thereby limiting how much time they can spend with each patient. The Hawaii experience with primary care capitation found substantial reduction in primary care visits (which saves no money under capitation), small increases in referrals to urgent care or the ER and to specialists, and no cost savings overall. Physicians may have more freedom to prioritize, spending more time with patients who really need it and less time with stable patients, but overall the effect is to push primary care physicians to take on more patients than they can handle and still provide high quality care. Now they are stuck in the “capitated payment

treadmill.” And now the incentive to avoid caring for sicker, poorer, and more complex patients is amplified.

In both cases, primary care physicians are stripped of professional autonomy and control over their time, contributing to widespread demoralization and “burnout.”

A Proposal for Fee-for-Service Based on Time:

For independent physicians, we recommend that a U.S. single-payer system should return to a standardized fee-for-service payment system but replacing the RBRVS with a fee-for-service system designed to be as administratively simple, objective, and incentive-neutral as possible.

This proposal would improve on the RBRVS and RUC fee-determination system in the following ways:

1. It would shift determination of relative values to the value of physician training and expertise instead of attempting to assign relative values to procedures themselves. It would use time as a common denominator linking the value of physician expertise to all services, cognitive and procedural. The actual value of a procedure depends heavily on the expertise of the physician performing the procedure and on each patient’s individual circumstances in any case.

2. It would improve the objectivity and accuracy of the practice expense component of fees and the geographic cost-of-living adjustment.

3. It would disconnect payment from the details of documentation and end over- documentation and gaming induced by pay-for-documentation.

4. It would compensate physicians for all professional time spent on patient care, including documentation, care coordination, alternative care delivery modes such as telephonic and telehealth based care, and administrative tasks, and would restore physician control over their time and schedules.

5. It would establish clear separation between the practice expense and work components of fees, and would require the single-payer to reimburse practice expenses at cost. This would create an incentive for the single-payer to minimize unnecessary administrative burdens and costs for physicians, and it would isolate the work component as nearly the entire determinant of physician personal income.

6. It would replace the RUC with collective bargaining at the national level to determine the work component of fees, which would determine physician personal income. Collective bargaining is intended to keep fees reasonable for physicians and balance the interests of physicians with those of the single-payer and taxpayers. Nationally negotiated fees would be subject to regional cost-of-living adjustments.

7. In order to correct the procedural-cognitive pay gap, it would reduce negotiation of fees to only hourly rates based on years of post-graduate training required for a specialty or sub-specialty and set the same hourly rate for all specialties with the same required years of training, instead of negotiating the fee for each procedure.

A “Fee-for-Time” payment system was first proposed by Tom Wachtel and Michael Stein in a 1993 JAMA article, entitled, “Fee-for-Time System: A Conceptual Framework for an Incentive- Neutral Method of Physician Payment.” Our proposal is an updated version of the same concept.

Instead of a proprietary committee such as the RUC setting the fee scale using “relative value units,” we propose retaining fee-for-service but replacing the RUC and Congress’ budget neutrality rules with collective bargaining to keep fees reasonable for both Congress and physicians, and vastly simplifying payment procedures to reduce administrative costs.

For practice expenses, we propose a more objective procedure by dividing the country into regions based on cost-of-living, each with a regional single-payer board that includes community representation. Instead of using surveys, these boards would determine the practice expense component of physician fees from regularly updated audits of full-time practice financial accounts by specialty or subspecialty within a region. Practice expense would be calculated by subtracting physician personal income from total practice costs. Malpractice Liability cost would be included in practice expenses based on these audits. The practice expense component of fees would then be standardized based on the average full-time practice cost for each specialty or sub-specialty within a cost-of-living region. Monthly specialty-specific average practice cost would be divided by 180 work-hours in a month to determine an hourly practice expense, and the single-payer would pay for this at cost, with no further conversion factor. Physician personal income would then depend almost entirely on the work component of fees.

We propose that the value of the work component be based on years of training required for each specialty or sub-specialty, with hourly rates linked to payment for specific procedures based solely on the time associated with each service or procedure. Specialties with the same number of years of required training would be paid at the same hourly rate, so as to correct the discrepancy between payment for procedures compared to cognitive services. The work component must include everything the physician does on behalf of their patients that requires their time and expertise, including documentation and care coordination time, telehealth, etc. To avoid encouraging inefficiency or over-documentation, paid time for documentation should be standardized and in proportion to the time of the visit.

For reasons of simplicity and to avoid disputes between patients and their doctors about how many minutes were actually spent versus billed, we recommend a prospective method (incremental, standardized times chosen prior to each visit) for assigning time billed for most services and procedures, but with the option of switching to a retrospective method (counting actual minutes spent) in case of complications and non-typical circumstances requiring more time from the physician than usual.

Cost-of-living adjustments to the work component would be applied at the regional level based on publicly available cost-of-living statistics instead of using the GPCI formula. The practice expense component of fees would not need any adjustment for cost-of-living because it would be based on audits of actual expenses that include cost-of-living.

The Fee-for-Time proposal requires assignment of a time for all physician services, both cognitive and procedural. The fee for a given service would be determined by applying the hourly rate for a given specialty or sub-specialty to the time associated with each service.

For cognitive services, the doctor, or doctor and patient together, would choose from an array of incremental times, such as in 15-minute increments. The rules governing payment would specify that the time increment billed includes reasonable documentation time, and if necessary, care coordination time, writing a letter for the patient, etc. Documentation requirements would follow the general principles for documentation of Evaluation/Management services from the CMS Evaluation/Management Services Guide, but the criteria for levels of service based on the details of documentation would be replaced with time-based codes. Since payment would depend on time only and not the details of documentation, the focus of documentation should return to patient care priorities and quality improvement instead of “pay-for-documentation.” For most office visits for cognitive services, a simple “SOAP” note (Subjective: Objective: Assessment: Plan:) should suffice. For unusually complicated patient situations, the doctor could document the nature of the complication and switch to the retrospective method of counting minutes actually spent.

For procedural services, uncomplicated procedures would be paid prospectively for a standardized time usually scheduled for each procedure. For most commonly used procedures, the times would be determined objectively based on audits of physician practice schedule books and electronic record time stamps, and the time associated with a given procedure would be the median time scheduled for the physician performing the procedure. It may not be possible for auditors to determine usual times for rarely used procedures, and in such cases determination of time would revert to the retrospective method of adding up time actually spent. The times for each uncomplicated procedure would be adjusted to include reasonable standardized times for documentation. As with cognitive services, in case of time-consuming complications the physician could document the complication and switch to retrospectively adding up actual time spent.

Setting hourly rates for each procedure:

For the work component of fees, we propose establishing a base hourly rate for a general practitioner with one year of post-MD training and a standardized incremental increase for each additional year of training required to practice a given specialty or sub-specialty. It may be reasonable to establish a higher incremental increase for the first 3 years beyond internship and a lower value for subsequent years. However, all specialties with the same number of years of required post-graduate training would be paid at the same hourly rate, with the exception of adjustments to correct maldistribution of specialties, which would be negotiated separately based on needs assessment supplied by the single-payer regional Boards.

A sub-specialist may treat some patients who only require the physician expertise and training of a lower level of specialization. For example, a cardiologist, who had to complete internal medicine training before sub-specializing in cardiology, may have a practice that is half cardiology and half general internal medicine. We suggest paying this physician at the higher cardiologist hourly rate for all their patients with a diagnosis relevant to cardiology. CMS, in consultation with their regional Carrier Advisory Committees, already establishes medical necessity criteria that include relevant diagnoses required for each procedure. For this cardiologist’s patients without a cardiology relevant diagnosis, we recommend paying at the internal medicine hourly rate.

Collective negotiation of hourly rates:

Standardized payment for the work component for doctors and other healthcare professionals requires a mechanism to keep payment in proportion to the training and expertise required for each profession, best accomplished with collective negotiation between the single-payer and organizations representing each profession. We propose requiring all physicians to join a professional organization, tied to licensure, that would be authorized to negotiate with the single-payer to establish the base hourly rate and the incremental increase for each additional years of training required for specialty or sub-specialty practice, with re-negotiation of these rates every 1-2 years, and at least annually for the first 3 years. Negotiation of fees would occur at the national level, and each professional organization would include all specialties and sub- specialties with the same professional degree. The regional boards would be responsible for determining community needs, and the work component could be adjusted by negotiated agreement to correct maldistribution of physicians and specialties.

Promoting professional ethics and quality:

Mandatory membership in a professional organization would enable this same organization to be charged with peer review and enforcement of professional ethics, deterring fraud and abuse, continuing medical education, and facilitating communication and referrals between physicians and other healthcare professionals. Peer review and discipline of unethical physicians would be much more effective if failure of remediation meant expulsion from the organization and loss of licensure. An effective peer review system should mean much reduced need for government agencies charged with investigation and punishment of fraud and abuse by physicians. All these functions would be covered by professional dues at no cost to the single-payer system beyond the practice expense component of hourly fees.

The professional organizations, along with independent publicly funded quality improvement organizations, could contribute to quality improvement projects, responding to demonstrated problems with quality or consistency of care and using metrics developed and modifiable by project participants, similar to the Intermountain model of quality improvement. This would require nominal block grant funding from the single payer. Quality improvement should be founded on the intrinsic motivation of professionals to improve patient care, not financial incentives and penalties.

Implications of single-payer reform using the Fee-for-Time proposal:

We believe that time-based payment of physicians within a single-payer system would be simple, objectively determined, and would require minimal administrative cost for both the physician and the single payer.

Billing and collections would become straightforward, because there would be a single payer with standardized fees and no patient cost-sharing. At the end of each day, the physician or office staff would enter the codes for procedures and services performed, the single payer would add up the time associated with all of them, and payment would be based on a standardized hourly rate. Physician offices should not need billers, coders, and scribes, or contracts with billing services, collection agencies, and revenue cycle management companies, almost completely eliminating any need for the extensive industry that has grown up around the complexities of billing and collections in our current multi-payer system. Only office staff directly assisting in patient care should be needed. Reduced office staffing and overhead means the practice expense component of physician fees could be reduced accordingly without affecting physician personal income.

Physician control of their time: The Fee-for-Time proposal specifies that the sole link between the standardized hourly rate for a given specialty and payment would be the time associated with each service or procedure. Since time-based coding would include documentation and care coordination time, there would be no uncompensated services or uncompensated physician time spent on behalf of patients. For cognitive services, the physician or physician and patient together would choose the time needed for each visit. For both cognitive and procedural services, the physician would have the option of retrospectively billing for time spent in case of time-consuming complications or crisis situations. A physician could schedule more time for a difficult patient knowing they would be paid the same hourly rate with no financial penalty for scheduling the time needed. Physicians, not the single payer administration, would have control of their schedules and time.

No pay-for-documentation: With the value of a physician’s time determined by the training required for their specialty, payment for all procedures and services would depend on time only, not the details of documentation, freeing documentation from “pay-for-documentation”that has been used in Evaluation/Management coding. The focus of documentation would return to patient care and quality improvement priorities. This should eliminate the pervasive problems now seen with over-documentation, cloned notes, and documenting things not actually done, resulting in improved accuracy and relevancy of documentation and markedly reducing information technology needs for billing purposes. Based on comparison with other countries that do not use pay-for-documentation, disconnecting payment from the details of documentation could reduce length of medical notes by 50-75% while keeping them focused on information truly relevant to patient care.

Incentive-neutrality and intrinsic motivation: Payment based on time would provide no financial advantage to perform procedures compared to cognitive services. Pay-for- performance schemes have been shown to be harmful to intrinsic motivation in health care, whereas the incentive-neutrality of time-based payment would leave the best interest of the patient as the primary motivation for choice of service.

Reduced fraud and abuse: Time is objective and inherently much less susceptible to gaming than pay-for-documentation, risk adjustment formulas, or determining prices of procedures based on assessment of physician skill, judgment, and stress. Other countries such as Canada, where the physician payment system is perceived as fair and consistent, report few problems with billing fraud and abuse by physicians.

Correction of disparities. Under a universal single-payer system using time-based fee-for- service, physicians would be compensated fairly and consistently for time spent on behalf of their patients, with no financial advantage or disadvantage to influence provision of services to any particular category of patients: complicated or straightforward, rich or poor, succinct or rambling in communication style. Uncompensated and under-compensated care would be eliminated. A physician could schedule more time for complex or difficult patients without financial penalty. Reduced practice overhead cost and equalized payment for all patients, with no uncompensated care, would markedly reduce barriers to establishing medical practices in underserved communities.

Simplified diagnosis coding. With elimination of “value-based payment” and no shifting of insurance risk onto competing health plans, hospitals, and doctors, there would be no need for risk adjustment, so maximum detail in diagnosis coding would not be required. Diagnosis coding for medical necessity and quality improvement should require only 3-4 digits of diagnosis codes, as is the case in other countries that use the ICD coding system.

Audits vs surveys. Regional boards within a single-payer system would commission audits instead of surveys to accurately determine the practice expense component of fees and the times to be associated with common uncomplicated procedures. Regional audits would be objective and not subject to biased surveys and the inter-specialty rivalries that now influence the RBRVS Update Committee (RUC). The up-front cost of audits would be greater than surveys, but this cost would be offset by elimination of the audits of E/M code documentation now being done by CMS, and by eliminating the cost of paying the AMA to run the RUC. Once the standard times for uncomplicated procedures have been determined, the simplicity and objectivity of time-based billing and collections and reduced opportunities for gaming and fraud should result in overall reduction in administrative costs.

Collective bargaining to keep physician payment reasonable. Based on international experience, unilateral control of physician fees by government under a single-payer system would likely lead to under-payment of physicians over time, as has happened in countries such as Italy, Japan, Taiwan, and New Zealand. Collective bargaining has worked well in Canada for both physicians and for keeping the Canadian single-payer system cost-effective. We believe collective bargaining would be essential to achieving widespread physician buy-in and for the sustainability of a single-payer system in the U.S.

Reduced malpractice liability cost. With a universal single-payer system, the medical care component of malpractice liability could be removed from litigation and placed under the universal system. This would markedly reduce both the size and frequency of liability claims, because injured parties would not have to sue to assure coverage of their injury related medical bills. The liability component of physician fees could be reduced accordingly without affecting physician personal income.

Sustaining physicians during a pandemic: A federally funded single-payer system would not depend on state tax revenues and employment status, so federal funding could fall back on deficit spending during an abrupt economic contraction. The Fee-for-Time proposal would not restrict payment to office visits only and would pay for everything physicians do on behalf of their patients, including telephone and telehealth-based care, documentation time, and care coordination time. Cognitive services could easily switch to other modes of delivering care during a pandemic without abruptly cutting off physician fee-for-service income. Office visits and elective procedures might be delayed during a pandemic but could be rescheduled when safe without the threat of loss of employer-based health insurance.

Conclusion:

We believe fee-for-service payment of independent physicians using the Fee-for-Time proposal would be substantially simpler, more objective, and less costly to administer than either fee- for-service based on RBRVS and Evaluation/Management coding or “value-based” payment with pay-for-performance and risk adjustment. A universal single-payer system that paid hospitals with global budgeting and physicians based on time and expertise, with standardized salaries for employed physicians and time-based payment for independent physicians, would likely achieve far greater administrative savings and substantially lower total cost than any proposal based on existing Medicare fee-setting policies or shifting insurance risk onto doctors and hospitals.